by sir Taki Theodoracopulos

It’s nice to be back in the old continent again, especially after getting within a couple hundred yards of the phoniest bunch of Hollywood East types, fakes with names like Pelosi, Schumer, Schiff, and their ilk. It made me fly out from the Bagel without mixed feelings for a change. America has become unrecognizable, a violent land where a Democratic Congress winks at riots and intimidation by the left, where career criminals are seen as victims, where one’s livelihood can end with a slip of the tongue. If that’s a free country, I’m Benito Mussolini, some of whose tactics would improve San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York. Over here, in lefty old London, everyone’s against Boris, but telling whoppers over a party or two or even ten cannot compare to Blair’s lies for going to war where hundreds of thousands died—or does it? I find it amazing that Blair is given the garter, and Boris might soon be shown the door. I am against lying, and didn’t lie when customs asked me if I was carrying almost forty years ago, but between a cake and thousands of dead, I’ll take the cake any day.

And speaking of leaders, Macron recently caught hell for asking us not to rub Putin’s nose in the dirt, but I’m afraid the frog was right. Biden knows how to spout slogans reading a teleprompter, Boris plays tough guy in order to make them forget the cake, but Macron understands the world. I haven’t read much about the French president, but I think I understand him. He’s a bit of a con man, but so what? I like Mme. Macron: She’s old and elegant, and she’s got good legs. A con man whom I met once and whom Macron reminds me of is André Malraux: fantasist, famous novelist, Gaullist minister, Cambodian historical treasure plunderer, self-invented Resistance hero, and air squadron leader for Republican Spain against my favorite—after Salazar—dictator, Francisco Franco.

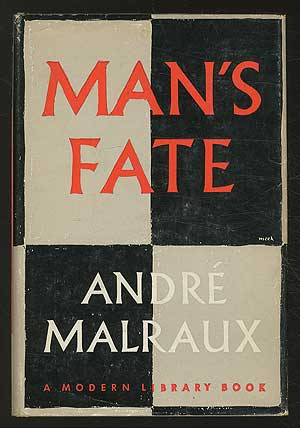

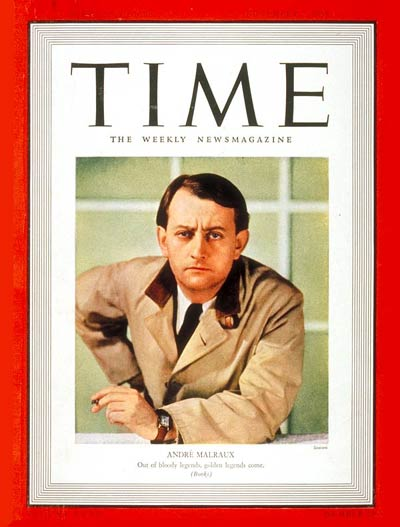

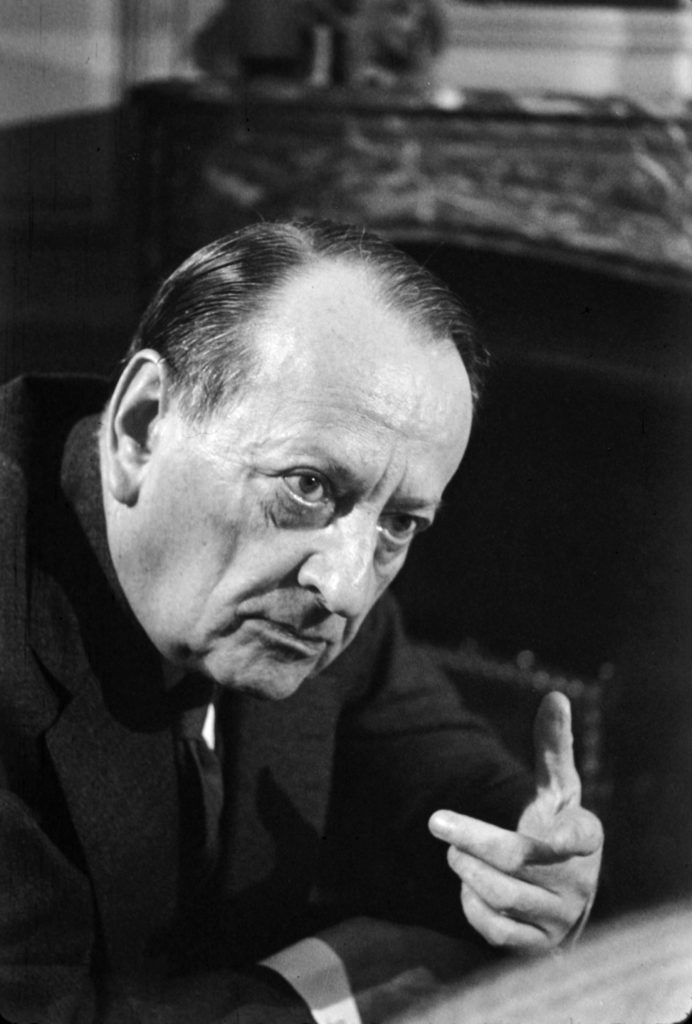

André Malraux was a man of action, that’s for sure, and an attention seeker par excellence. Unfortunately, I met him when he was a very old man, and half asleep or doped up while getting a lecture from my dad on the evils of communism. (The Greek minister of culture had brought him on board my father’s boat.) Malraux became famous early on after his book Man’s Fate was published. It was 1933, Malraux was a Marxist activist, and he followed up with Man’s Hope and other books. From early on Malraux was accused of being a man of image, not of ideas, by people who would soil their trousers if a shot was fired anywhere near them. Malraux admired and wished to emulate T.E. Lawrence. Unlike the tortured Brit, the Frenchman adored women, but identified himself as Lawrence’s son—symbolically, that is.

Malraux’s other hero was D’Annunzio, also a bit of a con man, but great, and Man’s Fate dealt with the revolutionary movement in China. He paraded around with a cape and a cane and had a true passion for art, and an even greater passion for the root of all envy. He satisfied the latter with an archeological expedition in Cambodia to rob Khmer temple ruins near Angkor. On a boat downriver with the loot, he and his party were arrested and spent a few months doing a Taki. His wife, Clara, got a petition going and he was eventually freed. Returning to Indochina, he became active in the Canton uprising and saw action. The artist and the man of action became one. From then on he was known as an exemplary revolutionary figure and a symbol of the Communist Revolution.

He sided with Stalin against Trotsky because the former looked like more of a winner, but then he redeemed himself in Spain, a Byronic enterprise, as he called it. Without qualifications, he took command of an air squadron and went on operations against nationalists but also filmed himself while bombing the enemy. His force of personality and courage prevailed over his inexperience. He made himself the hero he had pretended to be. When hostilities broke out with the Germans, he went to Lanvin and ordered a uniform. He was taken prisoner almost immediately.

Malraux joined the Resistance at a very late stage and greatly inflated his role in it. He met De Gaulle after the liberation and became his minister of culture in 1958. He had Paris washed, freshly painted, and spruced up. I remember seeing him disheveled and probably doped up leading an anti-student rally of pro-Gaullists in 1968. Eight years later he was dead, and twenty years later his remains were transferred to the Pantheon.

Malraux was an aesthete and self-invented. He lied a lot about himself, but his courage was undeniable. Why does he come to mind when I think of President Macron? I wish I could explain it, but I cannot. (Actually, Malraux more resembles Francois Mitterand—brainwise, that is.) What they have in common is an understanding and love for art and an opportunistic streak. Macron—like Malraux, who saw no glory in resisting the Germans, only death, but jumped in at the end when victory was assured—went after the brass ring after two French presidents had failed the office. The cultural after-effects of Napoleonic grandeur influenced them both. Malraux is long gone, but in the Pantheon. Macron is still to make his mark, but don’t bet against him. And we should take his advice and talk to Putin. It is not Putin who is defaming American history, destroying our monuments, and promoting gender fluidity to our children.

US President John F. Kennedy, Marie-Madeleine Lioux, André Malraux, US First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and US Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson at the unveiling of the Mona Lisa at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.photo credit : wikipedia.org