by George Archimandrites

On the occasion of the Ciné mode exhibition signed by Jean-Paul Gaultier at the French Cinematheque, its director, Frédéric Bonnaud, talks to us about the relationship between fashion and the Seventh Art, the mission of the cinema and the love of cinema.

How was the idea of the Ciné mode exhibition born?

The gallery has an important collection of costumes, as Henri Langlois, one of its founders, had a great interest in costumes and fashion. So this exhibition is based on our collection, which, as a living organism, is constantly enriched. But to present it in an attractive way, we have to find interesting angles, with a different direction each time. Because when you address the general public, you have to put on a real spectacle. And that is not easy. In addition, this spectacle must tell a story. So we turned to Jean-Paul Gaultier and asked him to tell his own story. It is the first time we dedicate an exhibition to someone who is not a director. Gauthier has strong ties to cinema and sees it with the eyes of the creator who comes from another place.

What are the commonalities between fashion and cinema as expressed through the exhibition?

What Gautier is primarily interested in is the spirit of the time, l’air du temps, because fashion and cinema reflect their time, capture and record its spirit. Their main common element is this. We must also say that fashion, and more specifically film costumes, is the expression of a certain cinema. Martin Carroll’s dress in Max Ophels’ The Fall of Lola Montes represents a different kind of cinema than a short gingham dress in a Brigitte Bardot film. On the one hand, we have the luxurious magnificence and on the other the popular element, every day, the lightness. The same applies to Greta Garbo’s dress in “Queen Christina,” on the one hand, and Monica Vitti’s short black dress in Antonioni’s “Aventura,” on the other. The history of cinema is seen by Jean-Paul Gaultier, who designs costumes for Seventh Art and loves films aimed at the general public.

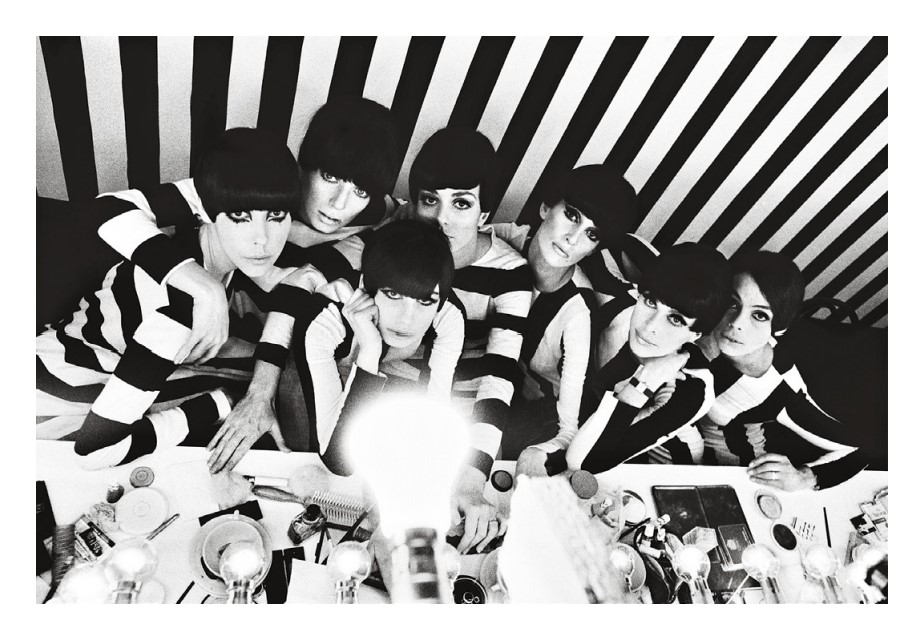

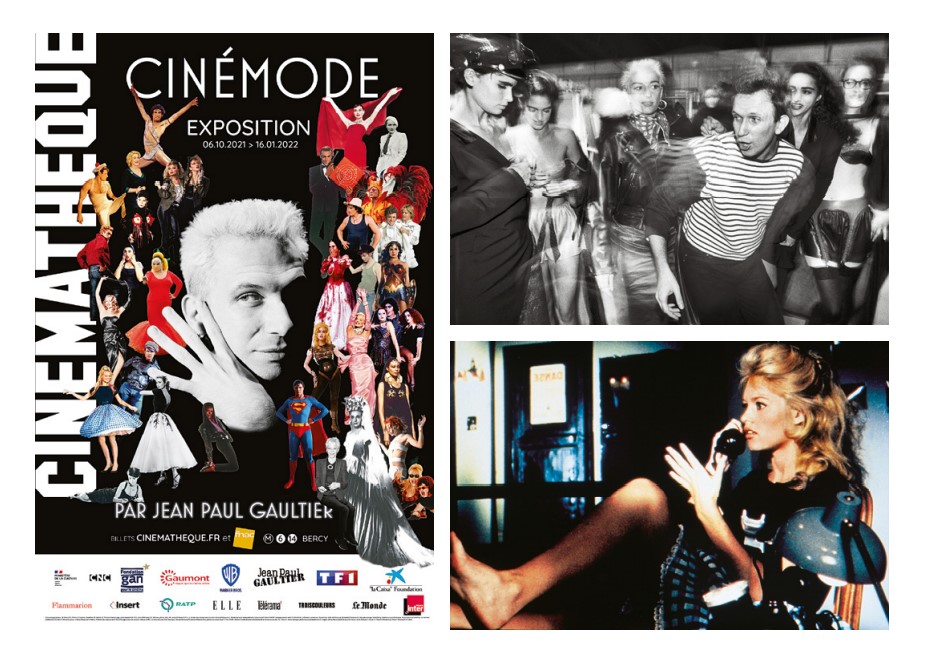

Left: The exhibition poster.

Top right: Backstage, Jean Paul Gaultier fashion show, prêt-à-porter women’s collection Barbès, F/W 1984-1985. © William Klein.

Bottom right : “Voulez-vous danser avec moi?” by Michel Boisrond. © 1959 Gaumont. Collection Gaumont.

Courtesy of Danièle Thompson and heirs Michel Boisrond and Annette Wademant

Do cinema and fashion in turn influence the spirit of the age?

Of course. This relationship works both ways. A typical example is “God Made Woman” by Roger Vadim with Brigitte Bardot, where the essential element of the film is Bardot herself. Vadim immediately realized that this girl marked a break with the way women had dressed until then, as well as with the way they were treated by society. And that was extremely important. Like a few years ago, the way James Dean moved in the films of Elia Kazan or Nicholas Ray was different from the way John Wayne moved in the westerns of John Ford. And so did Marlon Brando. Gautier is interested in this. He is interested in idols, Brigitte Bardot, Marlon Brando, James Dean, and Marilyn Monroe.

Left: Bastien Pourtout & Edouard Taufenbach. Marlene Dietrich Diptych: Mask and Narcissus, 2021. © Bastien Pourtout & Edouard Taufenbach, collection Pierre Passebon, 2021.

Top right: Pedro Almodovar, Victoria Abril, and Jean Paul Gaultier on the set of ‘Kika’, 1994. © Nacho Pinedo.

Right: ‘And God… Created Woman’, a film by Roger Vadim, 1956. © 1956 – TF1 STUDIO. – Courtesy of the heirs of Roger Vadim.-

As director of the French Film Archive, how do you see the public’s relationship with cinema evolving?

I think that cinema is of less interest to society today than it was thirty or forty years ago. Back then, when a movie was released in theaters, even when it was shown on television, it was the talk of the office and schoolyards the next day. Today our attention is fragmented on thousands of screens and the abundance of suggestions and stimuli is such that a new movie can hardly be a real event. The same goes for most Netflix series. It’s a rarity now. Cinema has been the most important form of popular entertainment in the world for many years. But I’m afraid that today it is much less. And this has nothing to do with whether a film is shown in the cinema, on the TV screen, or elsewhere. This battle is already over. The problem is what people see today on their computers, tablet, or mobile. And it’s clear that, for the most part, it’s not about movies.

Snapshots from the premises of the exhibition “CinéMode par Jean Paul Gaultier”, at the Cinémathèque français, whose president is the director Kostas Gavras. Copyright © la Cinémathèque français

And cinephilia?

Cinephilia is always there, but it follows the same path. When it appeared after the war, mainly in France, but also throughout the world, it was a very intense movement. Later, the French nouvelle vague, and especially the 50 signatures of Cahiers du Cinéma, was the first movement of pure cinephiles, as it was created by people who had never been assistant directors, nor had they attended film schools. They became directors by watching thousands of movies. It was the first time in the history of the seventh art that this happened, but it came from a pre-existing current of post-war cinephilic effervescence, which no longer exists. Of course, people always come to the film library, and we deal a lot with films that belong to the history of cinema, but a twenty-year-old in 2021 will not so easily see a black and white film, like me when I was twenty years old in 1987. Let’s not have any illusions. And as for silent cinema, let’s not even talk about it…

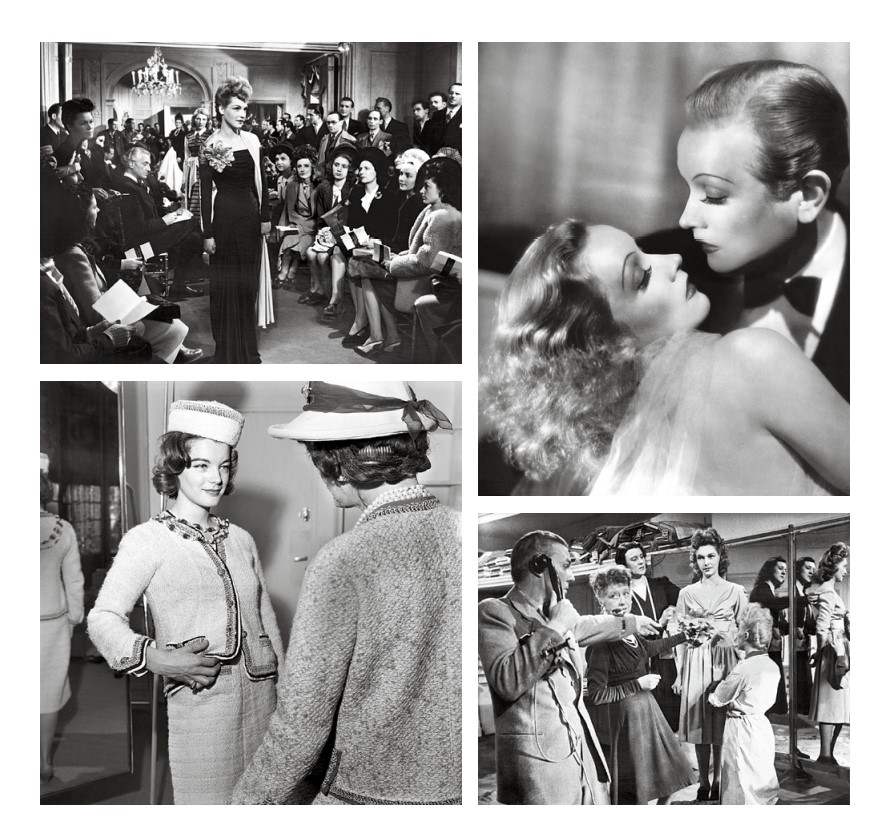

Top left: “Falbalas” by Jacques Becker, 1944, with Micheline Presle, Raymond Rouleau and Gabrielle Dorziat. Falbalas ©1944/STUDIO CANAL. Courtesy of the heirs of Jacques Becker.

Top right: Bastien Pourtout & Edouard Taufenbach. Marlene Dietrich Diptych: Mask and Narcissus, 2021. © Bastien Pourtout & Edouard Taufenbach, collection Pierre Passebon, 2021.

Right: Falbalas by Jacques Becker, 1944, with Micheline Presle, Raymond Rouleau and Gabrielle Dorziat. Falbalas © 1944/STUDIO CANAL. Courtesy of the heirs of Jacques Becker.

Bottom left: Romy Schneider and Gabrielle Chanel, 1961. © Giancarlo Botti/GAMMA-RAPHO

In this context, what is the role of the film library?

Our role is to continue to promote and support cinema as the most interesting of all entertainment. Of course, it is not a battle won in advance. The film library only deals with one part of the cinema. It doesn’t do film productions, it’s not a festival, and the new films it screens are few. Our goal is to help re-age the film-loving public and tell the world that to learn something about the history and art of the 20th century, it is good for him to see the films of Jean Renoir, Fritz Lag, John Ford or Alfred Hitchcock, which we show again and again. But we cannot perform miracles. We certainly contribute to the film education of the public, but we are like a drop in the ocean. We welcome around 40,000 students every year, which are few compared to the 65 million French people. Nothing has ever been done on a large scale about the image at school, and television, for its part, has stopped showing black-and-white films at prime time. So, in relation to all this, we are a minimal nucleus of resistance. We must understand that cinema is necessary as an art and as a spectacle. We need it to understand not only the world but also ourselves. The century is because someone like Alain René, for example, showed it to me through his films, talking about concentration camps, the atomic bomb, and colonial wars, creating a universal spectacle. In the cinema we show his films, with the hope that the viewers will also learn something, being entertained at the same time as the spectacle they offer. After all, this is one of the main aspects of our mission: to continue to show people that cinema is a need, a desire, and a pleasure.

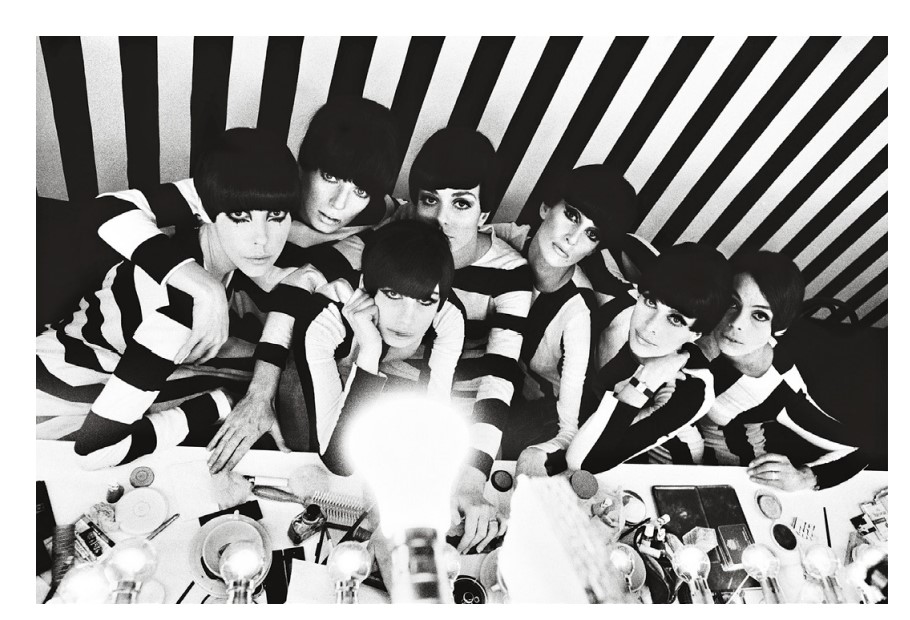

William Klein. Behind-the-scenes photography of the film ‘Qui êtes-vous Polly Maggoo?’, 1966. © William Klein/Films Paris New York.