by sir Taki Theodoracopulos

“Vivere pericolosamente,” was the creed of a bald, Italian dictator who attacked Greece in 1940 but ended up hanging from his ankles in a Milano square five years later. Benito did live dangerously, especially at the start of his career, but his sad end – hiding in a German uniform in the back of a troop-carrying truck – did not bode well for risk and adventure. Living dangerously is, of course, the greatest antidote to boredom, as far as I’m concerned, the latter being the greatest fear of modern life. As Ben Johnson said, “ imminent death concentrates a man’s mind,” and it also keeps one feeling alive and alert, hence challenging death is what adventure is all about. Since time immemorial adventure stories have captured the peoples’ imagination, starting with the greatest story ever told, that of the Iliad and the Odyssey.( Incidentally, anyone with a British passport living in Greece at present should hide it for fear of his or her life. The latest BBC series on the fall of Troy is more disgraceful than usual. Helen is an ugly Victoria Beckham, and Menelaos looks both gay and a Neanderthal.) Never mind. Death was omnipresent during the Trojan War, and it kept all the protagonists interesting to the last. Closer to our time, my hero, needless to say, is the greatest adventurer of them all, Ernest Hemingway, who is also the greatest writer of them all, bar none.

Papa Hemingway made narrative prose into a physical medium shorn of the cerebral and fanciful, apt for the Hemingway hero – tough, stoical, suffering, exhibiting what Papa called “grace under pressure.” Hemingway wrote, but he also hunted big game, fished, covered wars, drove an ambulance in battle, boxed, drank hard, was badly wounded in battle, fought bulls, and once gave the greatest answer to an indiscreet woman journalist who asked him if he had slept with many women: “All the ones I ever wanted, and a hell of a lot that I didn’t want.”

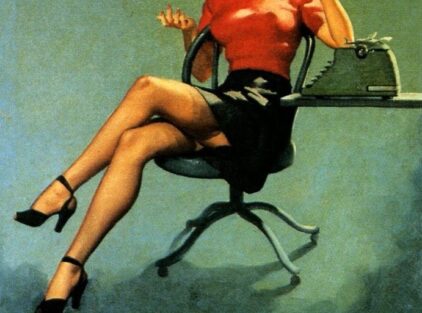

It is said that a typewriter is more lethal than a weapon, and I decided to become a writer on July 6, 1961, once the news of Hemingway’s suicide had reached me. His obituaries impressed me to the extent that my father’s business – he was an industrialist and ship owner – became a no-no. No shipping office in Piraeus, no country house north of Athens, became my creed. The writing life beckoned. My father was appalled, but I was his spoilt younger son, so he gave in. The next stop was Vietnam.

I arrived in January 1968, and was met by Joe Fried, the dean of the American press corps in the Nam, who told me that I would spend my first night in his house and then move on up to Phu Bai, in the north, where I would be a stringer for a wire service. (I was also a special correspondent for National Review, a conservative American magazine.) On our way into Saigon, Joe Fried’s wife Ruth, who had been on the plane with me from Hong Kong, and hadn’t seen Joe in five years, kept complaining about the rubble of the city. Once at home, she demanded air condition, but there was none. She kept on nagging in a very unpleasant way. Just as we sat down to dinner, the Tet Offensive began. All hell broke loose and a missile exploded on our roof tearing it away. I threw myself under a sofa but Joe, who had to file two stories per day for the New York Daily News, never missed a beat. “Are you happy now, Ruthie, now you’ve got air condition,” was all he said and kept on typing. This was my initiation to war.

I spent six long months up in Phu Bai and also covered the battle for Hue, the old imperial city the American Marines finally took back after a month long bloody battle. That’s where I met General George Patton, son of the great world war two general after whom my father had named a large tanker back in the Fifties. After Vietnam it was time for fun, and New York was where it was happening. Studio 54 became my home at night, and Studio was a change from El Morocco, where as a young man I had fought over Tyrone Power’s wife, Linda Christian, with Baby Pignatary, a famous playboy. (I was the first man ever to be allowed to stay after a fight in El Morocco, because rules were very strict. If one fought, one was banned for life. But my good luck prevailed.)

During the autumn of 1973 I was at the Athens tennis club hitting balls and laughing in the sunshine when Nassos Botsis, owner of Acropolis and Apogevmatini, suddenly showed up. Back then, newspaper owners were not in the habit of looking for journalists, they summoned them instead. But Nassos had a plan in mind. The Yom Kippur War was starting as the Egyptian and Syrian armies had successfully broached the Israeli borders and two terrific tank battles were under way. An El Al plane was picking up the Israelis who were draft age all over Europe and was making a last stop in Athens that night. “Will you get on it and file a story every day?” asked Nassos. Athens is always fun, but October can also be dull in the capital. My friend Zographos was overhearing the conversation and proposed something different. “Let’s go to Biarritz and gamble in the casino. I know couple of very pretty girls there whom I’m sure you will fall in love with.”

Well, you can guess the answer to that conundrum. I had been doing the casino scene with Yanni Zographos for a long time, so Israel it was. I got on that plane that night, landed in Tel Aviv and the next day I was driving up to the Golan Heights in a rented car. On the plane I had met a very old friend, Jean Claude Sauer, a photographer for Paris Match who had been alerted to fly to Israel while drinking at Regine’s in the company of the playboy Alix Chevassus, Maria Niarchos’s first husband to be. They were both drunk at the time but once they landed they joined up with me and Peter Townsend, the famous world war two airman who had been exiled from England after his failed affair with the Queen’s sister, Princess Margaret. Peter was writing for Paris Match.

The four of us were driving up towards Quneitra with Jean Claude going much too fast when I asked him to slow down, as Israeli ambulances were bringing back wounded and from experience I knew that more journalists get killed in car accidents during wartime than actual bombs and bullets. “Are you scared,” asked Alix in typical French arrogance. “Yes, I am,” I said and then suddenly all hell broke loose. Heat seeking missiles were coming down on us but Peter Townsend had the presence of mind to yell, “Turn off the engine and let’s get the hell out.” Which we did rather in a hurry and lay on the ground. Except for the French playboy who had frozen in fear in his seat and kept repeating in French, “I don’t want to die, I don’t want to die.” That is when Jean Claude made the greatest remark ever: “If he dies we’ll never be allowed back into Regine’s. Go get him.” “Never,” I replied. “You brought him, you go get him. Regine will always let me back in.”

I stayed in Israel for about one month, filed every day for Acropolis, and once I returned to Athens Nassos Botsis had me in his office and thanked me for my services. I wanted to be paid, instead. “You should be ashamed of yourself,” said Nassos, “your father has a lot of money, and you didn’t even bring back a girl from Israel for me, I hear they are pretty good down there.” So that was that. I had risked my life to find a girl for Botsis. I must say, it was so funny, I laughed out loud. “That’s the newspaper business for you,” said my dad.

Mind you, adventure came to me even before I knew how to spell my name. This was December 1944, and we lived in Patriarchou Ioakim, and the commies were knocking at the door. My father was on the other side of town fighting in Makriyanni, but he made it home for Christmas and even brought me a present. Looking back now that I’m 81 years old, it all looks like child’s play. The tyranny of convenience is the ever present danger. I do not use Google or Twitter and only use a mobile telephone when I’m on a boat on the Ionian Sea, yet the soft safe life is always dangerous. I still try and compete in judo and karate tournaments for veterans, but as of last year I have been deemed too old even for those. Overcoming worthy challenges and finishing difficult tasks is what my life is now all about. Brigitte Bardot was once a challenge, but she too is now too old. Women in general remain a great challenge but I suppose defeat where women are concerned is what makes us who we are. One has to accept the final defeat, that of death, but I had a hell of a good time challenging that old party pooper throughout my life. Embracing adventure is the key to a happy life.

Photo Credit: GettyImages/Ideal Image